• The study reveals that decision-making and movement happen simultaneously, constantly adjusting to new sensory information rather than following a sequential process.

• Both humans and rats adjust their movements in real-time, demonstrating the brain’s flexibility in integrating past and present sensory input.

• These findings could improve adaptive AI algorithms and contribute to therapies for motor disorders by enhancing our understanding of movement and decision-making dynamics.

Imagine you’re at the grocery store, reaching for an apple. In that split second, you’re not just moving—you’re deciding. But what happens if new information arrives mid-reach? Do you commit to the motion you’ve started, or does your brain adjust on the fly?

A new study published in Nature Communications by researchers Manuel Molano-Mazón, Alexandre Garcia-Duran, Alexandre Hyafil, Jordi Pastor-Ciurana, Lluís Hernández-Navarro, Lejla Bektic, Debora Lombardo, and Jaime de la Rocha, explores this very question. The authors, affiliated with the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica (CRM), IDIBAPS, and the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC), found that decision-making and movement don’t operate in separate steps. Instead, they unfold together, constantly adjusting in response to new sensory information.

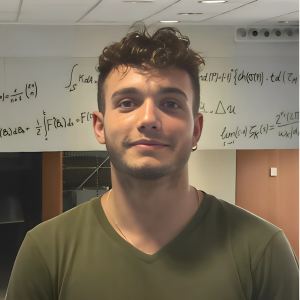

For decades, scientists believed the brain followed a two-step process: first, deciding what to do, then figuring out how to do it. This study challenges that assumption. By observing humans and rats, the researchers discovered that decision-making and movement evolve in parallel, seamlessly integrating past expectations with real-time updates. “The brain is often treated as a machine that processes information sequentially: first, it decides, then it acts. But the reality is more complex. These processes are in constant communication and can modify each other in real-time,” explains Alexandre Garcia-Duran, a PhD student at CRM and one of the study’s authors.

In the experiment, human and animal participants had to choose between two options based on auditory cues. Sometimes, the environment confirmed their expectations; other times, it threw them a curveball. Initially, both rats and humans moved based on prior assumptions, predicting the likely outcome before fully processing the sensory evidence. But when the actual sound contradicted their expectation, they adapted—sometimes even reversing course mid-motion in what scientists call a change of mind.

For example, rats would begin moving toward a specific port, expecting the louder sound to come from that direction. Yet within just 100 milliseconds, if the evidence pointed elsewhere, they would either slow down, speed up or abruptly switch direction. Remarkably, human participants showed the same qualitative behaviour when performing a similar task on a touchscreen.

Humans, like rats, balance prior expectations with real-time sensory input. Their accuracy improved as sound cues became clearer, even when reacting in as little as 50 milliseconds. When expectation and evidence aligned, movements were faster; when they clashed, movements slowed down. In about 7% of trials, participants changed their decision mid-movement—most often when prior assumptions were strongly contradicted by new information.

“A change of mind occurs when two sources of information contradict each other. Your expectations tell you one thing, but new evidence tells you another. If the new signal is strong enough and the cost of adapting is low, you switch,” says Garcia-Duran. He adds that it’s not just about how much information the brain receives but also the effort required to change course: “If you’re about to complete a movement and a contradictory signal arrives, you might just finish what you started instead of correcting mid-action.”

The Brain’s Parallel Processing Power

To understand this dynamic interplay between movement and decision-making, researchers built a computational model. Unlike traditional models that only predict final choices, this one captures how decisions evolve in real-time and shape movement.

The model accumulates sensory evidence through a drift-diffusion process, integrating prior expectations and real-time stimuli to determine movement direction. An urgency signal triggers an initial movement, which can later be updated based on further sensory input, either accelerating or reversing the trajectory if the new evidence contradicts prior assumptions. To estimate model parameters, a neural network is trained on 10 million simulations, approximating choice, reaction time, and movement adjustments for likelihood-based inference.

“ Richard Feynman once said: ‘What I cannot create, I do not understand.’ That’s essentially what we do with models—break down the fundamental mechanisms that drive behaviour,” Garcia-Duran explains. The model outlines two pivotal stages: an initial read-out, where movement is triggered by prior expectations and minimal sensory input, and a second read-out, where fresh sensory data fine-tunes the action. If the new evidence sharply contradicts the initial decision, the brain can even reverse the movement mid-action—an adaptive skill essential for survival in unpredictable environments.

To test the model’s accuracy, the team trained artificial neural networks on millions of simulated decisions, predicting choices, reaction times, and movement speeds. The results aligned closely with real-world behaviour: movements were faster when expectations matched sensory input and slower when they conflicted. This supports the idea that our actions aren’t pre-programmed sequences, but dynamic processes shaped by an ongoing accumulation of evidence.

However, Garcia-Duran emphasises that no model is perfect: “Models are never an exact replica of reality. Human behaviour is incredibly stochastic—there are so many overlapping processes that some level of variability is inevitable. The challenge is to isolate the fundamental mechanisms while keeping the model simple enough to be useful.”

Understanding how the brain continuously refines movement has implications far beyond the lab. These insights could improve robotic motion algorithms, making artificial intelligence more adaptive in real-world environments. They could also inform therapies for motor disorders like Parkinson’s disease, where both movement control and decision-making are impaired.

“The most immediate potential application is in clinical research. If we understand how this process should work under normal conditions, we can compare it with patients who have neurological disorders and identify what’s malfunctioning,” Garcia-Duran points out.

Looking ahead, the researchers want to explore whether the brain continuously integrates new information or does so in discrete steps. “One big question is whether we are constantly processing new evidence or updating in discrete bursts. What’s more efficient; absorbing all incoming information at all times or selectively updating when necessary? That’s something we still don’t know,” Garcia-Duran says.

So, the next time you hesitate mid-action or suddenly change course, don’t mistake it for indecision. It’s just your brain doing what it does best; keeping you on the right path, even when the world throws you new information at the last second.

Article reference:

Molano-Mazón, M., Garcia-Duran, A., Pastor-Ciurana, J. et al. Rapid, systematic updating of movement by accumulated decision evidence. Nat Commun 15, 10583 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53586-7

|

|

CRM CommPau Varela

|

Trivial matemàtiques 11F-2026

Rescuing Data from the Pandemic: A Method to Correct Healthcare Shocks

When COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted healthcare in 2020, insurance companies discarded their data; claims had dropped 15%, and patterns made no sense. A new paper in Insurance: Mathematics and Economics shows how to rescue that information by...

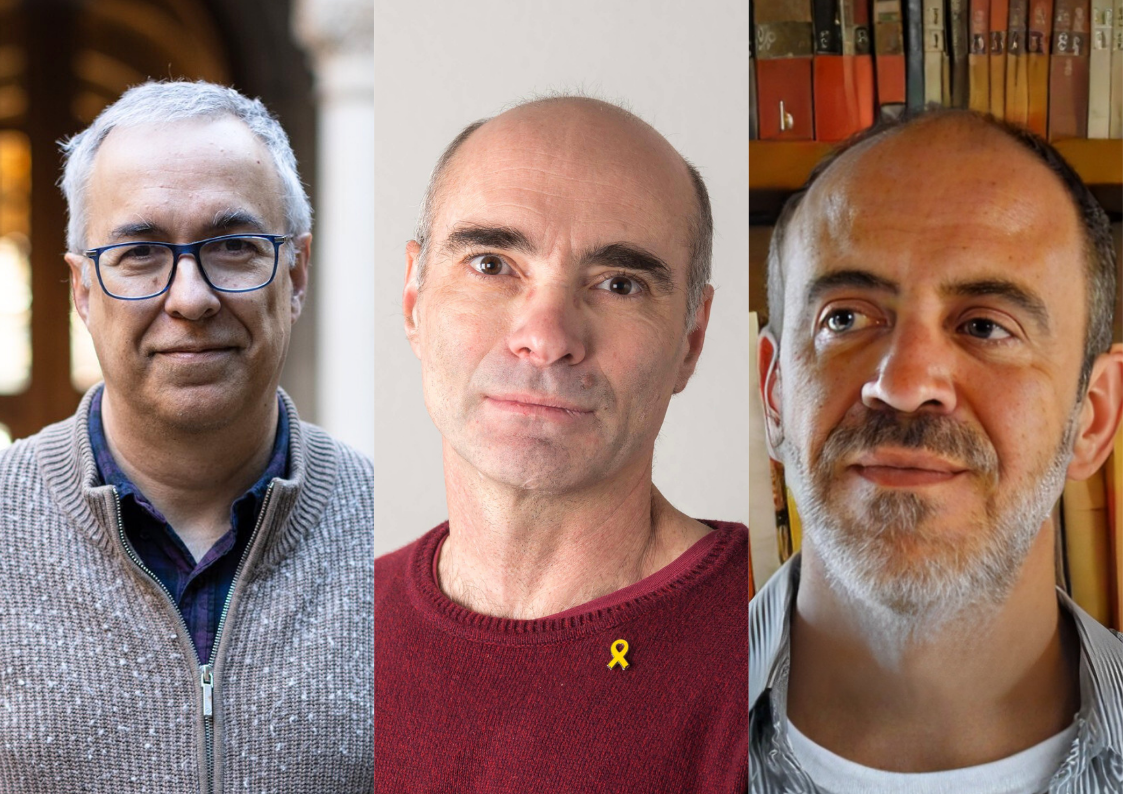

El CRM Faculty Colloquium inaugural reuneix tres ponents de l’ICM 2026

Xavier Cabré, Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà i Xavier Tolsa, tots tres convidats a parlar al Congrés Internacional de Matemàtics del 2026, protagonitzaran la primera edició del nou col·loqui trimestral del Centre el 19 de febrer.El Centre de Recerca...

L’exposició “Figures Visibles” s’inaugura a la FME-UPC

L'exposició "Figures Visibles", produïda pel CRM, s'ha inaugurat avui al vestíbul de la Facultat de Matemàtiques i Estadística (FME) de la UPC coincidint amb el Dia Internacional de la Nena i la Dona en la Ciència. La mostra recull la trajectòria...

Xavier Tolsa rep el Premi Ciutat de Barcelona per un resultat clau en matemàtica fonamental

L’investigador Xavier Tolsa (ICREA–UAB–CRM) ha estat guardonat amb el Premi Ciutat de Barcelona 2025 en la categoria de Ciències Fonamentals i Matemàtiques, un reconeixement que atorga l’Ajuntament de Barcelona i que enguany arriba a la seva 76a edició. L’acte de...

Axel Masó Returns to CRM as a Postdoctoral Researcher

Axel Masó returns to CRM as a postdoctoral researcher after a two-year stint at the Knowledge Transfer Unit. He joins the Mathematical Biology research group and KTU to work on the Neuromunt project, an interdisciplinary initiative that studies...

The 4th Barcelona Weekend on Operator Algebras: Open Problems, New Results, and Community

The 4th Barcelona Weekend on Operator Algebras, held at the CRM on January 30–31, 2026, brought together experts to discuss recent advances and open problems in the field.The event strengthened the exchange of ideas within the community and reinforced the CRM’s role...

From Phase Separation to Chromosome Architecture: Ander Movilla Joins CRM as Beatriu de Pinós Fellow

Ander Movilla has joined CRM as a Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral fellow. Working with Tomás Alarcón, Movilla will develop mathematical models that capture not just the static architecture of DNA but its dynamic behaviour; how chromosome contacts shift as chemical marks...

Criteris de priorització de les sol·licituds dels ajuts Joan Oró per a la contractació de personal investigador predoctoral en formació (FI) 2026

A continuació podeu consultar la publicació dels criteris de priorització de les sol·licituds dels ajuts Joan Oró per a la contractació de personal investigador predoctoral en formació (FI 2026), dirigits a les universitats públiques i privades del...

Mathematics and Machine Learning: Barcelona Workshop Brings Disciplines Together

Over 100 researchers gathered at the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica to explore the mathematical foundations needed to understand modern artificial intelligence. The three-day workshop brought together mathematicians working on PDEs, probability, dynamical systems, and...

Barcelona + didactics + CRM = CITAD 8

From 19 to 23 January 2026, the CRM hosted the 8th International Conference on the Anthropological Theory of the Didactic (CITAD 8), a leading international event in the field of didactics research that brought together researchers from different countries in...

Seeing Through Walls: María Ángeles García Ferrero at CRM

From October to November 2025, María Ángeles García Ferrero held the CRM Chair of Excellence, collaborating with Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà on concentration inequalities and teaching a BGSMath course on the topic. Her main research focuses on the Calderón problem,...